Chapter 9: A Doomed Outing in Vienna

I become Arp, imprisoned in the Pale Oaks, where I am free only to pet the Spine and stroll through a Viennese nightmare with Dubravka

I’ve been here long enough to finally become Arp, as the saying goes. Long enough, even—though now I may be saying too much—to begin to believe that I’ve been Arp all along, Spine a jettisoned appendage, a passing fancy from long ago. The tale of Spine’s return to Berkshire no more than a fireside yarn, told perhaps more than once to pass what has become far too much time in one place. Now, I won’t mince words, I’m old. Old enough to be shut away in dim concrete chambers, that much seems beyond dispute, unless my senses have abandoned me along with all those friends and colleagues I’d still like to believe populated my former life, and may populate it still, wherever it is now occurring.

I lie in my bed and listen to the drips dripping into my arm, and watch the identical twins—themselves getting on in years—parade the Emperor Franz Joseph down the hall on his litter, sometimes stopping by my room to pat my slick cheek with a felt hand and whisper, “Choose to believe you’ve survived what happened… choose to believe this is all that remains.”

The felt fingers streak down from under my eye to the edge of my lips, as if smoothing a mask that’s come loose, and I watch my tongue dart out to lick their leathery pads. The Quay Brothers smile and pull the hands back, moving the Emperor’s mouth so that it seems to whisper, “Now rest easy, Arp. Rest easy. After what happened, only rest can restore you.”

I try to rest easy, and sometimes I succeed, but other times a sweet, gamey reek dripping down from the ceiling and in from the walls invades my dreams and forces me awake, back to the sickroom where, I find, the smell is even worse. It’s coming from me, I sometimes think, though other times I’m not so sure. Other times, like now, I begin to wonder whether perhaps it’s the other way around, whether I am the only thing here that doesn’t smell that way. The only living tissue remaining… in a room of decaying flesh, in a world of flesh that’s long since decayed.

This phrase lingers in my mind as more puppets drift into view, detach my manifold catheters, and walk me out to the yard for exercise. Along the way, I reach out to massage the Spine, which runs the entire length of the hallway between my room and the main entrance of the Pale Oaks. Bracketed to the wall with brass ties, it is without a doubt the most sacred entity in the entire asylum, the charged object without which whatever tenuous arrangement is in effect here would surely collapse, just as—the memory returns to the peripheries of my mind, groaning awake as if from a coma—Spine himself collapsed when he…

I grasp onto the spindly nerves extending from the Spine and pull them, kneading, doing all I can to shock some life back into them, in hopes of thereby shocking myself back to…

The puppets disapprove. I can see them shaking their heads in a whir of string, their beady eyes swirling, and I know, from long experience, that it is not wise to anger them. So I clamp my mouth into a smile, docile and humiliated, as I seem to be more and more often these days.

Still, as I run my worn-down fingers along the Spine, nearly bone on bone, dry nerves encircling my knuckles, I begin to feel some of what it feels, an itch and a tingle and a warmth near my tailbone. By the time we make it outside, I feel even more like the only living tissue remaining than I did when I was doped up in bed.

The only living tissue, that is, except for Dubravka, presuming she feels the same way I do. Outside the main gate, my puppets deposit me in the courtyard just as her puppets deposit her, each of us presented on cue to the other. And then, as always, it’s just the two of us, strolling off into our allotted recreation hour as the sun begins its afternoon descent, and the season changes from summer to winter, papery snow sprinkling in from the sky.

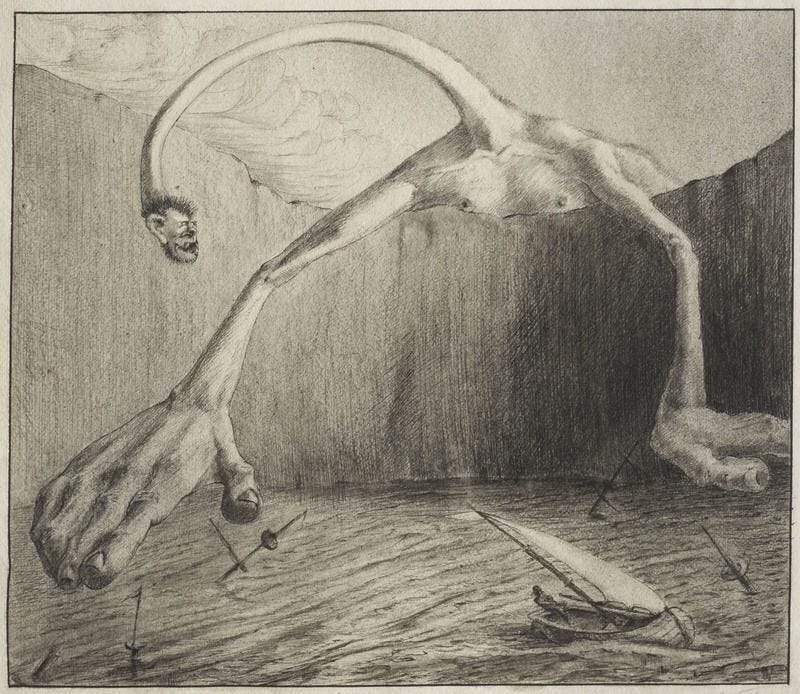

Earlier in my stay—or in my gauzy, narcotized memory of my stay—there were others here, perhaps as many as thirty, but now it’s only me and her, walking side by side past the miniature cabanas that serve as tombs for these others, lined up along an expanse of blue tissue paper, meant to simulate the ocean far below, at the bottom of the hill or mountain whose summit the Pale Oaks commands. As we pass by, we see puppet-sized skeleton faces observing us from the windows of these cabanas, pressed right up against them with their fingers on the sill beneath their chins, their eyes vacant but still mournful, their skulls swiveling from left to right.

I’ve learned to ignore them, but Dubravka still waves, willing to extend them the benefit of the doubt regarding the possibility of life after death, or after whatever it is they’ve gone through and that we might be soon to go through ourselves, though we leave this thought unspoken by mutual, and likewise unspoken, agreement, as we pass the two remaining cabanas, empty and waiting.

*****

Past this ersatz seaside cemetery, she and I begin to shrink, our spines contracting into our necks while our shins pull our femurs down, rendering us about half our former size, small enough to pass through the gates of the scale model of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where—we suddenly find ourselves able to recall—we met as students and became lovers, spurring one another on through the long, demoralizing years of labor on our first professional artworks—mine, the first of several animated films that would eventually ensure my worldwide reputation and guest professorship at BerkshireArts, in the then-still-extant United States; hers, a thousand-foot tall shaking pole at the top of which, allegedly, a sentient ape climbed and climbed, working against the clock in hopes of reaching heaven by hand.

We walk now, past the imposing facades of the painting and the sculpture halls, the University Museum with its priceless collection of Bellmers, Kubins and Kokoschkas, the screening rooms, the dance and drama theaters, as we quiver (or: something quivers) in our shrunken bodies, sweating out our memories of our infirmity in the Pale Oaks and beginning to reanimate the students we were then, two Croatian emigres in bustling, fin-de-siecle Vienna, away from home for the first time, probing the surface of the wider world for cracks through which we might make our way in—as if, the thought strikes me as humorous now, the inner circle of the Art World were coterminous with the Hollow Earth of ancient lore.

“I keep forgetting which century it’s the end of,” Dubravka says, right on cue. Like an implanted memory-trigger, the phrase flashes us back to our earliest flirtation, as eighteen-year-old students, when, if the triggered memory can be trusted, she used the line for the first time, and, like now, I was immediately charmed by its combination of cynicism and naivete.

I nod, also on cue, and picture the 1880s and the 1980s flowing together into a stagnant pool of blue tissue paper—a pool, indeed, whose only feature is its stagnation, its proud refusal to flow over the edge into 1900, or 2000, whichever round number we believed spelled the Terminus of All Decline, the actual End of the End, that which all our efforts were aimed at avoiding. Avoiding, I think, or perhaps, on a more fundamental level, of finding a means of profiting from. The Terminus for which we were determined to become the Official Spokespeople, members of that coterie of artists imbued with the rare power to Reify the End while everyone else merely suffered through it.

Now it starts to feel like our minds as well as our bodies have been miniaturized and handed over to some power outside the scene, directing us on our romantic stroll across the campus, following in the precise physical and mental footsteps, so to speak, that we followed last time, to say nothing of the time before that.

“Accept that these are your memories,” a voice says, emanating from another tissue-paper pool, this time in the courtyard between the main dining hall and the dormitory where I lived for my first two years, before moving into an apartment in a seedy, nocturnal district of outer Vienna, where I continued to live until my first two films were finished and sent on their way, bobbing along the currents of reputation until my turn in the spotlight came around. The Zagreb International Animation Festival, I think, the Grand Hall of the…

“Focus!” the voice interrupts. “Accept that the Ending, so long as you remain here within it, will never lead all the way to the End.” This jogs something in my memory, as it clearly does in Dubravka’s—she shudders as it travels through her still-shrinking head, a bullet-sized lump that I try not to stare at—and we press close together, embracing as if for the first time.

“Accept that this scene is what you miss the most,” the voice continues, “the very place to which you’ve been desperate to return, and you will be permitted to remain within it.” Now it no longer seems foreign, though I can’t tell what language it’s speaking. Whatever it reminded me of a moment ago has been forgotten, and now it sounds like my own voice in my own head. My own thoughts, I think, same as every minute of every hour of every day I’ve been lucky enough to live out on this plane so far.

Dubravka holds my hand tighter and says, “Shall we stop in someplace for a cup of hot chocolate?”

I feel myself weakening as I continue to shrink, the buildings at the outer edge of campus taking on uncertain dimension, some looming up like grey citadels while others wilt like weeds, but I manage to nod, and let her lead me through one of the gates and out into Vienna, itself of jagged and inconsistent dimension, some of the buildings colossal and others diminutive, while still others are missing, X’s on the ground in the lots where—if I’ve been here before—they used stand, and may one day stand again.

We stroll through Vienna in the twilight as it begins to snow, falling more and more in love as the last of our memories of the Pale Oaks—and the final years in Berkshire that led up to our confinement there—steam out of our heads. For a long, blessed interlude, we are free of memory entirely, free to enter the hot chocolate shop in the present tense and sit at a cozy table in a carpeted back room, surrounded by recessed shelves of used books, Mann and Kleist and Stifter in green and crimson Morocco.

An elderly waitress brings our mugs when they’re ready, covered in whipped cream and curled shavings of dark chocolate, and she smiles in a loving, grandmotherly way that I try not to see as condescending, or as a sign that she knows something we do not.

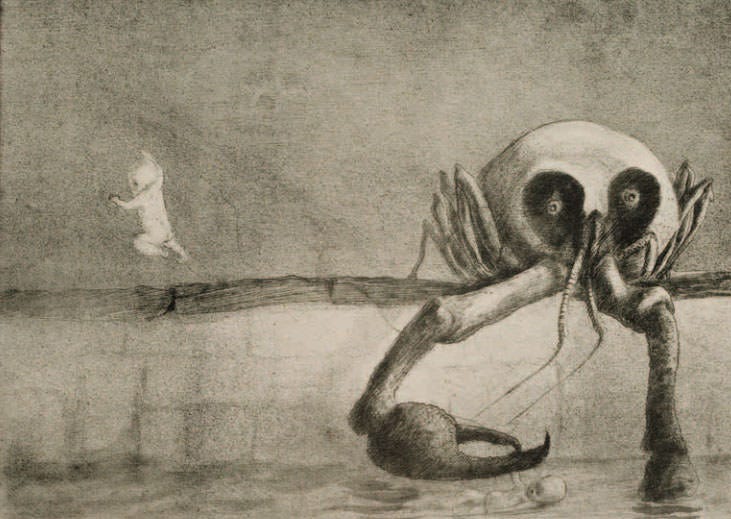

“And so, what I’m thinking is,” Dubravka begins, launching back into a discussion of her thousand-foot pole and the ape that’s still climbing it. I try to listen, but I can feel the hot chocolate dribbling down my chin and into my collar, and I can tell that, no matter how hard I try to swallow it, I will never manage to, because there’s nowhere inside me for it to go. Literally nowhere, not even a hollow space. I can just barely remember having had a bodily interior, but the memory is long gone, lost in that same interior, fated to wander into eternity and never be found. I press the cup to my mouth and feel a flat, solid surface where the orifice should be, a drawing of a mouth, or even less than that—two lines forming a wobbly oval.

I press the cup harder between these lines, determined to pry them open and, if need be, invent a biology on the spot.

Dubravka stares at me, clearly concerned, but, as I begin to smash the cup against the plane of my face, scattering what’s left of the liquid inside, I can see that her concern likewise lacks a third dimension. Both of us cutouts, I think, as heavy, wet chocolate runs down my front and onto the Biedermeier chair I’m perched on. Her eyes flash and flicker, filled with some third-party’s notion of how concern ought to be represented.

“Let me out!” I scream. “Let me out of here right now!”

After I’ve screamed so long I can no longer tell if any sound is escaping me—long enough, even, to begin to feel insane for imagining that any sound ever did—the grandmotherly waitress returns flanked by looming nurses, ten or fifteen feet tall, and I watch them hook Dubravka under the arms and lead her out of the café. I try to see through the windows to find out where they’re taking her, but night has fallen along with the snow, so all I see is fluttery darkness and eerie moonlight. Then the nurses are back in the café, likewise hooking me beneath the arms, while saying, in unison, “Beg us. Beg us to take you back there and we will.”

I hold out as long as I can, determined now to keep my mouth sealed, much as I was determined a moment ago to pry it open.

But the nurses, so tall now their heads lie flat against the ceiling, like balloons after a child’s birthday party, repeat their ultimatum. “Beg us to take you back to the Pale Oaks and we will. Your warm, soft bed. Your soothing, salty morphine. The Spine with its many trailing spindles, dry and taut as baling wire. Refuse, and you will remain here, abandoned to the frigid wastes that are closing in, while your hot chocolate gets colder and colder and colder.”

This utterance destroys the room. The walls fall outward, away from one another, knocking over all of Vienna. Soon, I’m alone with the nurses in a dark forest, the only light that of the shining eyes of thousands of wolves, together radiating the glow that I’d previously attributed to the moon.

“Say the word,” the nurses repeat, loosening their grip on my paper arms, just enough to show that they’re capable of abandoning me, that no puppet string binds us together. “Say the word now, or say it never.”

I again wait as long as I can bear to, as the wolves draw in, their yellow eyes forming a mutant galaxy’s worth of weak moons, and, though I know I’m going to say the word, I wait until the wolves are close enough to smell, a moment longer than I waited the last time I was in this predicament. Just before I forget how often I’ve been here and end up back in my warm morphine bed once again, I think, if I can be proud of anything at all, I can be proud of having waited as long as I have.

Then I reach up and pull the paper edges of my mouth apart, ripping the substrate of my face and causing blood to rain down into the hardened chocolate collar around my chin and throat. Spluttering as the hole widens, I hear myself beg, “Alright. Take me back there. Take me home to the Pale Oaks. My warm bed, my salty morphine, my…”

The nurses reach out, stuff my bleeding mouth full of ether-soaked cotton, and catch me as I nod off, falling what feels like a long way, through their arms and all the way down into the bed that seems always to appear at the very bottom, just before I land on something hard.